Into the Deep–“Pelagic Magic”

So enjoyable and comfortable and easy was this first night dive that I decided to follow it immediately with another, one that promised to be equally enchanting judging by its name, Pelagic Magic.

At dusk we meet under a street lamp at the pier in Kailua-Kona. A small group. Just five of us including me. We mill about uneasily like thugs waiting for the boss and our night’s orders. A white van pulls up. A short, thickset man exits the driver’s side, a tall, stocky man from the other. The driver instructs us to sit on the asphalt under the light and he begins to talk. His speech is clipped, like that of a New Yorker. His name is Matthew. He’s the dive master.

“We’re going offshore,” he says, “to where there’s a convergence of ocean currents. I don’t know where this will be; it’s different every night, could be five miles, could be ten; I’ll have to feel for it. Once there we’ll anchor into the current with a parachute. Then we’ll throw your asses over the side. You’ll be attached to 50 feet of weighted line. You’ll have a dive light. It’ll be dark and the bottom will be 5000 feet below your fins. If you drop the light, no one’s going after it. If you drop the light, you’ll be blind. So don’t drop the light. Here is what you’ll see if you don’t drop the light.”

For twenty minutes Matthew moves through a binder of slides–pictures of tiny translucent animals, alien in form and name–pyrosomes and pteropods, salps, heteropods, and siphonophores. He says there may be box jellies (get out of the way) and comb jellies and sea horses, paper nautiluses, squids of various sizes and types.

Matthew closes the binder.

“This is my dive. I’ve been out there at night four or five hundred times. These little animals are likely all you’ll see,” he says, “but know there’s other stuff. It’s the big ocean we’ll be in–this ain’t no Disney Land Manta dive. Blue marlin, sword fish, sharks will probably be hovering beyond your light. They don’t want any trouble. Your are attracting the types of animals they eat–they’re just looking for a free meal. If the squid get thick and fast, they might hit you hard as they run from the big fish. It’s dark; you’re in black; they can’t see you. I’ve been hit in the chest, in the neck. It’s like running into a bowling ball. You’ll scream. I do. Can’t help it. Focus on your regulator. It’s your friend. Keep it in your mouth. Always keep the regulator in your mouth–you can spit that thing out when you get home.

“And don’t pee in your suit. Remember, to the predator fishes humans swim with the grace of a wounded cow. Pee in your suit and suddenly you smell like a wounded cow too. That’s like chumming the water. Don’t do it.

“After a time you might think it’s all kinda too much. That’s OK. Once on this dive we dropped on top of schooling white tip sharks. The sharks weren’t all that jazzed about us. But what were we suppose to do, go somewhere else? About ten minutes into the dive one of the sharks slammed my mask. I know it was purposeful. And at that point I knew the dive was over. You’ll know when your dive is over too. Surface whenever you’re ready.”

“What’s the name of this dive?” I softly ask Matthew’s companion. He is sitting next to me. His name is Scott, also a dive master.

“We call it a black water night dive,” he says.

“I thought this was Pelagic Magic.”

He pauses, thinking, and then, “Oh yes, that’s what they call it in the office.”

“One other thing,” says Matthew. “I’m not going down with you. I’m driving the boat tonight. Scott will guide you. He’s the new guy, so try not to cause any trouble.”

*****

We speed directly away from the pier and out into the open ocean where calm harbor waters are replaced with a small swell. The wind moves into the north. Our boat is taking spray over the bow.

When the swell achieves a certain force, rolling the boat in a particular way, we’ve gone far enough, says Matthew. The boat stops, the parachute is heaved over the side, and as it unfolds the bow slowly moves into the wind.

The mood aboard is somber. Or at least the five of us who are customers pull on our wet suits in a slow quiet contemplative manner that suggests somberness, that suggests we may soon be asked to walk the plank. Matthew rigs a weighted line for each of us, evenly spaced along the boat’s sides, as Scott gets into his gear. And without much fanfare we queue at the stern and splash. I am last. I walk off the platform into pitching nothingness and descend.

To call the first few minutes of this dive disorienting is to use a terrestrial, known and easy word for an utterly weird experience. “Orient” (east) refers to finding oneself relative to the rising sun, so, strictly speaking, I am not disoriented in this dark of night. I am, however, utterly lost. I can see the shaft of water defined by my light. It is bobbing randomly below me because I can’t find the grip, though it’s strapped to my wrist. I can see the white line dropping into the abyss. My ears begin to compress, so I know I am descending, but how far? I see the weight bag on the end of my line pass quickly (50 feet). I grab for it. I miss. My inflator has gone missing. I forget I am wearing fins and can swim up. I just sink. Then my tether catches and I stop with a jerk. The inflator reappears and I add a little air to my vest, just a little, I think, and suddenly I rocket up and break the surface.

This is not good.

I focus my light on the weight bag at the end of the line, using it as a judge of depth, and descend again. This helps, but still I seem to zoom up and down, realizing only after some time that the bag attached to the boat is pitching and rolling in the surface swell. This fight to achieve stabilization seems to go on for hours and is, in fact, but fifteen minutes. So says my watch when I finally have the wits to check it.

Only then do I begin to see the darkness.

My light extends out some thirty feet, and miniscule creatures float through the beam. Below me Scott hovers untethered, facing the surface, moving with ease. I turn toward the bow and there are my fellow divers, drifting, limbs extended into undefined night at the end of white strings. It is as if we are spacewalking in a sky without stars.

When the animals appear, they look just like Matthew’s slides, but are no more familiar for it.

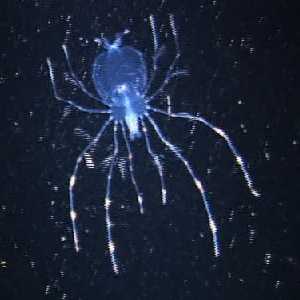

First I see a two dimensional spider, almost entirely clear, wafer thin, four legs protruding forward, four aft, a small thorax and an abdomen large and round. It twitches, turns sideways and disappears, reappearing as it turns.

Then a comb jelly fish, fully extended, its inner strings churning like generators, its overall shape that of a futuristic space ship.

Then a bunch of oblong grapes whose cluster is about the size of a cantaloupe, again translucent and glowing coppery on the inside around which swim tiny silvery, almost flat fishes.

Then a blunt-nosed cone with the overall look of a raspberry inside of which swims a translucent shrimp. The shrimp exits the raspberry, climbs on top, does some business and returns before shrimp and raspberry drift beyond my light.

Glowing twitching worms. Animals that look like triangular razor blades with fiery edges and antennas at the corners that shoot sparks. Jellies the size of peas. Egg sacks in the shape of perfect spheres.

–

On and on.

Long intervals separate sightings, intervals of silence, darkness, and cold where I am sure time is stuck, unable to pass for lack of anything to pass by. Yet when the dive ends after 65 minutes, it is as if it had been but an instant.

If the Manta dive felt like a revivalist church service, this dive had about it aspects of the purely private. Like climbing a mountain or sailing across an ocean alone, it was a solitary reaching for the utterly-other-than while hoping it wouldn’t bite your hand off.

Either dive I would do again in a heartbeat, but it’s on a blackwater night dive that one really has a sense of seeing deeply into…the deep.

*****

The short video below from 2010 does a very nice job of capturing the experience. Same boat, dive master, and location.

—

This video fails to capture any of the feelings of weirdness, but the photography is much better and contains most of the creatures I saw from below.

*****

Please visit www.konapelagicmagic.com for Matthew J D’Avella’s stunning photography of animals encountered on these dives.

More information on the dive can be accessed at www.jacksdivelocker.com.

Into the Deep–Manta Night Dive

For Sharkman, who will get his chance. (Don’t miss the video at the end of this article.)

One night after the Mauna Kea ascent found me 40 feet underwater, again gazing skyward with a group of toursits like myself. But we were not searching the heavens for mythic beasts. We wanted real ones. We wanted Manta Rays.

The scuba trip was advertised bluntly as the Manta Night Dive, the only such dive in the islands and famous for it. It had developed accidentally, we were told. Some years back the Sheraton Hotel installed large lights along its bit of coast to illuminate for its guests what is, after the sun sets, utterly black and undifferentiated sea. The lights attracted plankton, which attracted plankton feeding animals, like Manta Rays, and the Mantas attracted … divers. Soon every dive company in Kona had a Manta dive, requiring other locations to be found or manufactured.

Our boat of fourteen divers arrives late. Garden Eel Cove (one of the alternate Manta sites) just off a rocky bit of coast near the Kona Airport, already contains eight other boats bobbing on the swell. We moor, suit-up, and dive the cove in the remains of the day so as to have our bearings when night falls. We find a bouldery, coral bottom that gives way to rubble without coral that then falls to sand. Here Garden Eels protruded from their hidey-holes like short lengths of licorice rope swaying in the current. We return to the boat as an orange sun touches the horizon.

Aspects of the Manta dive have about them the aura of communal religious ritual, and in keeping with such there are lots of rules. As we suit-up in the dark, our dive master, Mongo, reviews these twelve commandments in detail.

1. Go right to the bottom; do not dally.

2. Stay on the bottom and in your assigned station; do not wander up into the water column where you may be crashed into.

3. Shine your flashlight straight up. Hold it in front of your face, and resist the urge to move it around (this aids in the build-up of plankton intensity and thus Manta attraction).

4. Sit still before the Mantas arrive; sit still after they arrive. Sit still.

5. If you think a Manta is about to collide with you, continue to sit still. Mantas know what they are doing. If one does collide with you and rips your mask away, do not also spit out your regulator as this will ruin your dive and piss off those who must rescue you.

6. Resist the urge to touch the Mantas as they pass inches from your face. This could injure their slimy, protective coating.

7. Do not exhale bubbles into the Mantas mouth. They breath water, not air. But DO NOT hold your breath as they pass as this, combined with all the other excitement, may lead to fainting.

8. Do not shine your light in the Manta’s eyes, nor into your dive master’s eyes, nor into those of your neighbor diver. Doing so is unkind and may result in your being punched (by your neighbor).

9. If you think you have been bit by a manta, remember that they don’t have teeth. If you think you have been stung by its long tail, remember they don’t have stingers. Manta’s don’t have weapons. They can’t hurt you.

10. Be in charge of your own air. Do not ask your dive master how much air you have because he too has forgotten his prescription mask and can’t see the gauges any better than you.

11. When in transit to and from the boat, stay with your group (denoted by differently colored lights attached to the tanks of the different groups). Divers who return to the wrong boat will be made to return to the right boat via the “surface swim of shame”, which will be filmed and posted on YouTube.

12. Scream as much as you want, just stay put.

By this time more boats have arrived and the tiny cove is out of moorings–boats are tethered in-line to each other. The water top is a chaos of bobbing black suits and small lights glowing different shades of pastel.

Our group of seven divers splashes last. Once on the bottom, we find the pews are full; the congregation already seated. Mongo moves us to a rocky patch in the back and plants us in our spots. The cove floor now contains well over a hundred divers distributed in a rough circle, all facing inward. Each carries a bright light, as do the many snorkelers floating on the surface whose beams move in every conceivable direction as if we, together, are here for the purpose of creating a large, aquatic disco ball. So much light fills the cove that it feels like an unevenly lit room. Very possibly we are inside an aquarium. Everywhere rushes of bubbles cascade toward the surface, sparkling in the frenzy of light like showers of stars falling up. Schools of silvery fishes add the flash of comets.

The cove is positively abuzz.

And in this state we wait. For maybe ten minutes. Only the younger divers are impatient. They wander off and are returned to their seats by Mongo with a hand motion, “Stay!”, that one might use on a dog.

Slowly from the dark perimeter a dark, undulating form. Slowly and steadily it flies into the light, its wings curving and releasing, tipping and turning without flapping like a bird’s, and yet the animal moves forward as if otherwise propelled. Slowly it flies through the whoosh of bubbles and out the other side into the dark. Then nothing; nothing but the sound of collective breathing.

Then from another point of the unlit perimeter, two more shapes approach and waft themselves into the light as if they are so much liquid smoke. I grip the rock with one hand and shine my beam with another and wonder how to describe these animals.

They are most like giant bats in shape, but they don’t remind of bats at all, rather what comes to mind is that their heavy, deliberate, yet weightless grace is much like that of flying elephants. This analogy is inept and ridiculous and I laugh, almost coughing up my respirator, yet it stands as the best I’ve come up with.

Then there are three Mantas, then five, swinging through the circle. Most have a wingspan of six to eight feet, their great, white mouths, large enough to swallow me head and shoulders, agape, toothless cottony cavities bordered by antenna-like scoops. The bellies are white and spotted with grey in a way distinctive to each individual. The top of the animal is entirely black; clinging to it are tiny, shrimp-like parasites. The narrow, ray tail contains no stinger and is as long as the animal is wide.

The plankton is beginning to concentrate. I can see small points of light jetting around in my beam, and squirrel fishes dodge in and out grabbing a meal when the Manta’s aren’t close.

At eight Mantas I lose count. Now they appear to be everywhere in the dome of light. Some swoop low over the divers (several pass so close over my head I can’t help but duck) while others somersault just below the floating snorkelers, rolling again and again and again. After a time their collective movements, still slow, still graceful, begin to carry a sense of urgency, and at some point there are so many Mantas that a few misjudge their trajectory and collide.

I lose track of time. I forget to check my air. And then Mongo is tapping me on the shoulder. He collects our group for the remainder of the dive, and we wander off into the dark where we find a cuttle fish hovering in anticipation and a slipper lobster running away.

Near the boat plankton suddenly intensifies. The animals are a cloud in my light and I can feel them pricking the skin of my bare hands. Two Mantas are somersaulting below me, closer and closer until they bump and rub my suit and I pull my light against my chest for fear it will be swallowed. Over and over they roll and I watch and watch at the surface while holding the boat’s ladder. I am the last diver and realize I have been so for some time. There are no other boats in the cove save ours, and still the Mantas roll and spiral in my beam. Then there is another tap on my shoulder. Again it’s Mongo, now standing on the stern in shorts and t-shirt “Randall, can we go? We’re all very sleepy.”

Bite Me!

Three days on the hook at Kealakekua Bay, where Captain Cook was killed in 1789, and now am nestled back amongst the Sport Fishing fleet in Honokohau Harbor. Here the water is clear if the sky is not and the docking fee is but $6 a day.

My wife arrives this evening by plane from New York via San Francisco and Los Angeles, and though she will not be staying with us, I’m deep-cleaning Murre as if she were. Mold has grown on the ceiling during the rainy months in Kauai. And dust continues to exploit its evolutionary niche no matter how predatory is the ships’s broom. Murre may or may not be cleaner after my work, but her heavy odor of Pin-Sol gives evidence to effort.

A sign on a nearby boat defines this place: “Kona is a drinking village with a fishing problem.”

The fleet departs daily before I wake and returns in the early afternoon to its own cleaning ritual of first the prizes, ahi, mahimahi, wahoo, and then the boats. A quiet day on the dock always ends with a party, regardless of the catch.

But today is different. Today one of the Bite Me charter boats landed a 465 pound Marlin.

The Bite Me operation is impressive. A small fleet of charter boats in harbor, its own restaurant with its own dock and, conveniently, its own fish hoist.

“The first 50 pounds of catch goes to the customer,” says a less successful captain, a beer in one hand, a hose in the other on a boat now smelling strongly of bleach, “the rest goes to the restaurant.”

“I hooked a fish as big as that last week,” he continues. “We fought him for an hour and a half and he flipped the hook right here,” and he points the the boat’s stern.

“How old do you think that fish is?” I ask the skipper.

It seems a natural enough inquiry.

“I dunno,” he replies, “never raised one.” He laughs by way of suggesting that was the dumbest question he’d ever heard, and then gets to the nub of the matter. “Sure taste good though.”

Fishing boats in harbor outnumber sailboats twenty to one, and the only other active cruising boat here is directly ahead of Murre. She is Tao, Chris and Shawn aboard. From Oakland by way of Mexico and soon headed to New Zealand via the Cooks, Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji.

We joke that we have the state of Hawaii to ourselves. Cruisers who arrive here often depart as soon as possible, having seen but one island and its one marina. Admittedly island hopping in Hawaii presents unique challenges (see last post), anchorages are often exposed and rough, and official rules are not cruiser friendly (though the officials themselves are sweet as pie after a time). But rugged beauty there is in abundance, and we marvel at the islands’ bad reputation. Which is not to say we are disappointed. More catch for us.

Night Hopping to the Big Island

March 27

It wasn’t that the wind had come fair for a passage to the Big Island; this was simply the fairest it had been in days and days. Small craft advisories in all channels had been cancelled. Easterlies of 25 and 35 knots had given way to north easterlies of 20 with a promise to restrengthen by the weekend. I had plans to meet Joanna in Kona the first week of April–this could be my only shot.

During the day I secured the boat and then lay early in my bunk, wide-eyed and worried. The alarm wakes me at 0200. By 0300 I’ve made coffee, kitted up in boots and oilies, and we are underway, motoring below Diamond Head for the Kaiwi Channel to Lanai, Maui’s Fish Hook (the constellation Scorpius) our guide, bright and high. Wind in the channel comes on slowly but is 17 knots from the northeast by 0600, Murre close hauled at nearly five knots. By 0900 it is gusting 22 but the wind has veered more into the north as we come behind Molokai and so I can ease our single reefed main and jib. Still, the rail is under, water everywhere.

Around 0800 I see whale spouts and soon there are two dead ahead but five boat lengths off. Both disappear without sounding; Murre and I pass and we never see them again. Then at 0906, I am coming back on deck from breakfast and see a glossy black line in the water two boat lengths ahead. Before I can jump to the wheel a great fluke thrashes the ocean in front of the bowsprit and the whale dives, leaving a slick like that of a ships.

An hour later the wind abruptly eases to 6 knots from the east, and we are motoring with sails up. I’ve made it through, I think. But the lull is brief. Dark water ahead and the flash of white caps. When we are hit it is wind 20 gusting 25 from the east, forcing us to motor-sail as close hauled as can be for the last six hours to Kaumalapa Harbor on Lanai’s south side, tiny, rock-bound, with wind shooting down the canyon from the east and then the north. But secure, quiet, welcome. Anchor down by 1630. 57 miles in 13 and a half hours.

–

–

We had fixed some leaks, but the weather finds others. On this crossing, water came in the port Dorade vent. We were on port tack and heeled heavily. The vent only drains to port, so filled with spray and overflowed into the cabin.

Lentils for dinner and I am asleep an hour after sundown.

At 0200 the alarm sounds again, and again, by 0300 we are in the offing, making for the lee of Maui under a brilliant sky, the cliffs of Lanai dark and tall like the walls of an ancient fortress, wind soft on the face like breath. We motor around the island. The red lights of the turbines on Maui’s western mountains and the glow of the small town down and to the right. Phosphorescence bubbles by, tiny suns are born, go super nova, and return to the void.

At 0640 the sun tops Haleakala and within moments there is wind on the nose at 15 knots. I try wearing a diving mask to keep the continuous waves of spray from my eyes, but the sun strikes the water on the mask surface full-on and is blinding, reducing visibility to nothing.

By 0800 wind veers northeast and we sail for an hour; then it dies. I motor past Molokini, and, as it is early, I turn to take a spin through the moorings, already full with the day’s dive boats. Something strange about the water dead ahead. “Sailboat Sailboat go OUT and AROUND the reef!” calls the radio. Hard to port. I miss the reef, but have lost my taste for a spin through the mooring field.

1030. Anchor down at Makena in sand at 17 feet. Calm. I swim in the coral garden for an hour then fall asleep on the bow, waking to an uneasy motion. A chop is building suggesting wind from the northwest, and Murre is exposed. By noon the wind has picked up to 10 knots, but I can see much more headed our way. I weigh and we move around Pu’u Ola’i Hill to Olenoa (“Big Beach”) just as white caps pour into Makena. Wind tears through the rigging all afternoon, but Pu’u Ola’i knocks down the chop and Murre rides easy.

I have lentils for dinner again, but they are not tasty. I am not hungry. By sundown I am in my bunk–alarm set for midnight. The infamous Alenuihaha Channel is next, our last barrier to the Big Island’s lee.

These are all night crossings–The Kauai Channel, The Kaiwi Channel, The Alenuihaha–for a reason. Trade winds sweeping across the vast ocean meet the high islands of Hawaii and funnel around. Wind that is a mean velocity of 15 knots on the ocean can increase in the channels to 25 knots and more as it squeezes through. But it is not the wind we worry about, it’s the waves that, in such tight quarters, grow high and steep and out of proportion to their cousins on the open water. Similar issues face the cruiser in the Sea of Cortez as wind funnels down from Nevada and Arizona and sweeps the narrow water between the Baja peninsula and Mexico, creating what locals call “Buffaloes” for the way breakers charge along in a heavy rushing stampede.

In Hawaii the worst is the Alenuihaha because it is between Maui’s Haleakala at 10,000 feet and the Big Island’s much taller Mauna Kea. Wind velocities here are pushed beyond measure. Breaking seas of 12 and 15 feet are not uncommon. One deep-sea tug captain reports a big growler took out his wheelhouse. Again, I lay in my bunk not sleeping. I decide in my worry that Alenuihaha is Hawaiian for “the great alligator she is laughing.” Ale (gator) Nui (great) haha (obvious). Nevermind that alligators don’t grow here.

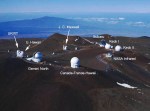

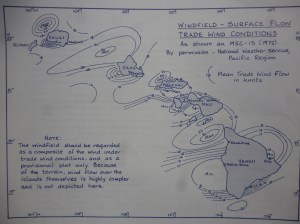

The Alenuihaha Channel from space. The camera is facing southwest with the Big Island on the left, Maui, Lanai, Molokai to the right. Note the flow of trade winds into the channel as indicated by the funneling of cumulus clouds. Maui's Haleakala at 10,000 feet can be seen as well as the Mauna Kea crater on the Big Island at 14,000. Upalo Point juts out into the channel and Murre's destination, Kailua-Kona is the dark spot of coast directly above Mauna Kea.

And the day heightens the effect. The sun heats the land pulling air up, making the wind funnel the channels with even greater speeds. So we wait for the blanketing of night, and we hope. I have to remind myself there are no small craft advisories forecasted. I have to remind myself we have worked UP to Maui for a reason and that an attack from here means we should take the Alenuihaha on a broad reach. Still, I have already double reefed the main.

I wake before midnight without the alarm. Both groggy and tense. Boots, long pants, double sweater (in the tropics? Yes!), oilies. Coffee. A snack bar in each pocket. A litre of water tucked under the rail. We are in the offing within the hour. Zero wind. The white water that blew out Makena anchorage in early afternoon is gone. But the channel is something different. There will be wind there. There is always wind in the channel.

By 0100 it has come. We are passing the point and wind is 20 gusting 22 northeast. And the waves? I can’t see them. The moon set an hour ago. Be we are close reaching. Course 160 degrees true. Perfect. Easy now, but we are not quite out from behind big Maui.

0200 and Murre is chopping along, keeping our course and racing at 6 to 6.5 knots. A little wet, but nothing to expectation. Heavy water over the top with a slam only twice. I make log entries from under the hood and note how luxurious it is to be dry and out of the wind. A grand night above: Mars is in Leo; Saturn in Virgo; Corvus points to the False Cross (I think). And Maui’s Fish Hook, our guide. So few constellations naturally look like the thing they represent. Orion, the Big Dipper, Maui’s Fish Hook–familiar friends.

Wind increases by 0300. I go back to the wheel to take in more of the jib, but I lose the sheets. By the time I’ve rolled up the entire sail, they have knotted together in what looks to be a decorative braid three feet long and so Gordian I think I may have to cut the line. It takes fifteen minutes for the knot to unravel.

Speed same. Course same. The chart plotter sounds an alarm and shows a small cruise ship on an intercept, the Safari Explorer doing 9.5 knots. She passes, a wink on the horizon. I sit under the hood and find I am worrying about tsunami debris approaching the Canadian coastline, ahead of my projected return course later this year. A fishing trawler washed into the Japan sea a year ago is now derelict and drifting 150 miles off Queen Charlotte Sound. Earlier predictions suggested debris would not arrive till late in the year. I would just skate through. But now? Not.

0500. Wind up and down between 20 and 25 but northeast. Blessed northeast–it is making this a comfortable run. Keeping our course takes fiddling. I opt for easing the main or drawing it in from under the hood for fine adjustments. Quite a roar in the rigging. Dawn coming. A haze over Mauna Kea, the island a slate slab. And with first light, the waves. Which are small now. We are behind Upolu Point twenty-five miles to windward. It must already be knocking them down.

0630. Sunup over the Big Island. Maui still visible astern. Wind 25. We are fast. Murre rides easy.

An hour later wind has dropped to 10 knots from the east, and an hour after that it has vanished into thin air. We are still twenty miles from port and must motor. Now the island is completely obscured by vog (volcanic smog/fog). Upolu Point is gone. Moana Kea at 14,000 feet is gone. No island is visible until we are eight miles out and still we motor in a dead calm. An anti climactic end to an otherwise lovely crossing.

We glass into Honokohau Harbor, just up from the town of Kilua-Kona, at 1430. 62 miles in 14 and a half hours.

Mucking About in Honolulu

Murre departed Pokai Bay on March 18 for a short passage of but 25 miles to Honolulu. It was nothing to write home about. A lovely two hours of sailing on a broad reach below the lush canyons of Wainea followed by five hours of motoring dead into an easterly.

That knuckle of land where the coast turns from trending south to due east I call Ship Point after the tanker that seems ever to be moored there, two miles off, and requires going around. Here is where the wind came hard on the nose. It took two hours to approach and finally pass the motionless hulk against which waves crashed as if she were a stretch of long, black cliffy coast. A crewman on the bow wearing an orange jump suit sat back and watched and Murre rose and fell and threw water like a shaking dog. It would be impossible to describe the patience required to sit at the wheel and take spray in the face for five hours as one’s charge, not charging on so much as plunge diving, averages speeds easily outmatched by the tottering old.

Slowly the skyline of Honolulu came into focus; incrementaly slowly the buildings grew in stature. The expected lee of Diamond Head was no lee, and the wind only eased as we entered Ala Wai Harbor. As we entered our slip there was none.

Easterlies of some force kept us bottled in Honolulu for a week. And though I was eager to continue on to the Big Island, there are worse places to be bottled, especially when a small white lie told to the state marina people regarding Murre’s overall length resulted in our being assigned a smaller than appropriate slip there, with the further result being that we were forced to remain at the Waikiki Yacht Club. Here the bartender greeted me with “Welcome back. How was Kauai? G and T, right?”

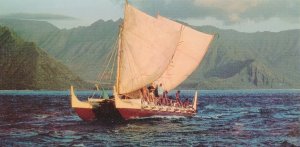

But waiting was not wasted. I varnished the toe rail, recalked the leaking cuddy, and, after nearly wrecking it, managed to rebuilt the seized anchor windlass. By way of diversion I visited the Bishop Museum one day and the next discovered the Polynesian voyaging canoe, Hokule’a, floating beside her dry dock on Sand Island. Happily, it was a Sunday and she was covered with a busy volunteer crew. As I stood gawking a large shirtless Hawaiian man walked over to introduce himself. “You checking tings out, brah?” he began, smiling broadly. He was Kai, had sailed on the Hokule’a to Okinawa in 2009 and then to Palmyra Atoll near the equator some years later. “Hokule’a saved my life,” he said. “I was young, doing bad tings. Then I met Nainoa. He told me that it’s easier to know where you are going if you know where you have been. So I joined the Polynesian Voyaging Society. The Hokule’a is our heritage.”

There is general scholarly consensus that Hawaii was settled by Polynesian peoples who set forth from the Marquesas Islands around the time of Christ in large, twin hulled, voyaging canoes. The impetus for these voyages range from the related reasons of overpopulation, famine, and power struggles. But consensus stops there as one school of thought holds that Hawaii was discovered by trial and error (with the repeated loss of life this method implies) and the other that ancient Polynesians were excellent navigators and could transit the Pacific at will.

In the early 1970s this latter group formed the Polynesian Voyaging Society to test their theory. A replica canoe, the Hokule’a, was built and a Hawaiian who could navigate in the old way was sought. But none existed. The art had been lost to Hawaiians. In fact, only one man in all of Polynesia was known to navigate by sea and stars alone. He was Mau Piailug (and here) from the Carolinian Island of Satawal. He was propositioned by the Society and agreed to the task, then brought to Honolulu where he learned the stars of this new area at the Bishop Museum planetarium.

Aboard Hokule’a he and crew departed from Hawaii for Tahiti on May 1, 1976 and arrived safely a month later, having sailed from one small spot of land to another over 2600 miles of open ocean. No navigational aids were used but stars, sea, wind and the occasional bird; no technology but that in Mau’s head.

Nainoa Thompson, a young Hawaiian crew member on that voyage, watched Mau with awe and vowed to return this ancient art to his people. He spent months in the Bishop Museum planetarium learning the night sky, memorizing hundreds of stars for the north/south transit. Then Mau returned to Hawaii to tutor young Nainoa on using these stars for position and course.

In 1980 Nainoa successfully navigated Hokule’a to Tahiti and back based on a system blending Mau’s techniques and that of his own devising.

Since then he has navigated Hokule’a over most of the Polynesian triangle and has taught many other Hawaiians the old method. He has become somewhat of a legend in Hawaii. Months ago I sat in a Super Cuts chair in Kauai and, conversation with me usually having but one trajectory, the young cosmetologist and I soon began to talk about Polynesian voyaging. “Have you heard of Nainoa Thompson?” asked the woman who had earlier admitted she’d never been off the island. “When I was a kid he would come to our class. We’d ask him how he pooped in an open boat. We were kids, right? That was our big question. He said you just jump in the water.” She laughed. “He’s very kind. And humble. Soft-spoken.”

He was soft-spoken, at least. Nainoa moved about the decks of Hokule’a the day I met Kai. He was slender. He moved slowly, with intent, giving instruction softly to one crew member, patting the next on the back. He was now mid-fifties and greying. Not the canoe’s captain but more senior, in charge of not just the boat but the project, the heritage.

The Hokule’a began to warp out for a practice sail and Kai jumped aboard. “Kai, I’d love to join. Do you need crew today?” I asked.

“Sure brah,” said Kai, still smiling. “On Tuesday and Thursday nights we meet here. We clean the boat, we varnish and make lines. Then in a few weeks you sail.”

–

–

–

–

–

Kauai to Oahu with a note on groceries and baseball

A casual reading of current posts may suggest I am simultaneously in Saudi Arabia and Hawaii. So warns my wife. Knowing my gifts as she does, she flatly insists this is impossible. One time it so happened I reported I was at the Safeway at Market and Dubose when in fact I was at the Lucky on Masonic and Lyon. She had told me to go to the Safeway at Market and Dubose for the soy milk (light) and toasted squares of seaweed in a box (teriyaki) for her and the week’s coffee for me. When I called and said it wasn’t there she said, “Where are you?”

“At Safeway,” I said.

And she said, “No you’re not. Safeway has what I want.”

And I said, “OK.”

And she said, “What’s the sign say?”

And I said… Well, for a moment I said nothing. What did she mean by sign? I looked up and sure enough the sign above the vegetable section declared in big, friendly letters, “Lucky. Your Low Price Leader.”

So I said, “Lucky. Your Low Price Leader.”

And she said, “See. If you were at Safeway it would have read ‘Safeway. We have what Jo Jo wants.'”

So I went to Safeway, and it had what Jo Jo wanted. But the sign said something different.

Point being one of clarity. I’m in Hawaii now. Sadly, the Saudi trip is in the past, though I will continue to report on it in the coming weeks.

_____

We (Murre and I) are on the move again. Are anchored at Pokai Bay, South Oahu, to be specific. A cruise of the Hawaiian islands has commenced with a near-term goal of reaching Kona on the Big Island in the next week or so.

_____

March 14

2:15am. Departed Nawiliwili for a crossing of the Kauai Channel for Oahu. This was my only break between early week moderate to strong trades and forecasted late week strong trades. A lull. Grab it. Hawaii’s channels can be nasty places for a small boat.

I planned one long tack SE as close on the wind as could be born. Simple, in concept.

But I have not sailed for months now. In the boisterous seaway of a moonless night I kept fumbling the lines, missing my grab, tripping on stays. At the main mast I pulled hard at what I thought was a halyard, and the spinnaker pole came tumbling down on my head.

With sunup, winds NE and steady at 20 knots with prolonged gusts to 25. Steep, crashing chop. Murre straining under a too-heavy press of sail. A reefed jib and a reefed main. But this was necessary in order to power her nose out of the swell, I reasoned.

Murre complained anyway. Her bowsprit spent more time underwater than above it. The main cabin ports on starboard were constantly seeing blue. My new cuddy did a wonderful job of keeping water from coming in under the companionway hatch and its hood kept my head dry (I typically sit in the hatch while underway), but every time we took a big splasher over the top, all the water that landed on the hood funneled into my lap and then below. I’d built the spillway wrong–not directed far enough aft.

And such a jarring motion. Holding on below took all fours. I couldn’t cook, could barely bring myself to eat. I felt seasick for the first time since leaving San Francisco.

Murre could not hold her course. By mid channel we were six miles to lee of the mark. Then eight. By sundown we were abeam Pokai Bay, but ten miles below it. A man of courage would have kept sailing–he would have climbed to the island tack upon tack–but that same man would not have made port at all that night.

I started the engine and for another three hours we motored at three and four knots into the wind, engine lugging and smoking, to my great concern.

Anchor down at 8:30pm. I went right to sleep. The passage of 72 miles had taken 18 hours.

And woke with a splitting headache. I’d had no coffee the day before.

But a blissful dawn at Pokai (and a cup of coffee) erased my head’s concern. I spent the sunny morning overhauling the seized anchor windlass and the sunny afternoon in the clear water cleaning Murre’s bum. The engine lugging, I found, was due to Kauai barnacles that had encrusted the propeller. Now scraped away.

In the evening I tuned the radio to a local college baseball game. A no hit yawner left the announcer extolling the virtues of the pitchers, the same virtues, inning after inning.

Then in the sixth the UCLA Dons scored on a base hit followed by a double play ball that the University of Hawaii Rainbows short stop threw into the stands.

When the ‘Bows came to bat, they answered with a lead-off base hit. Two perfect bunts, both botched by the pitcher, loaded the bases and a bobbled then dropped sac fly sent two men home.

The announcer for the ‘Bows, suddenly awake, exclaimed, “Oh my, this game can turn on you like a dime!”

I’ve heard tell of sportscaster mixed metaphors but had never fished one fresh from the sea, all shiny and still beating. The crowd continued to make its noise; the sportscaster continued to exclaim. It seemed only I had caught this small prize.

A dinner of pasta, red wine, and a book, Ben Finney’s SAILING IN THE WAKE OF THE ANCESTORS, ended a perfect day.

end

Kauai Abnormal

Thursday, March 8

Aboard Murre, Nawiliwili Harbor

2am. I wake to wind and heavy rain. Too bad. I’ve not put the boat cover back after the day’s work. Then lightning. Not close. Often no thunder. But it’s like paparazzi flashes. I count seconds–one-and-two-and-three-and–and see white light on every upbeat at least. Sometimes it comes in bursts that defy counting. I dash on deck to spread the cover. Rushing to finish before the lightning nears. Breathing heavily though the work is not strenuous. Thinking how dumb it is to be on deck, naked, in torrential rain…in a lightning storm. I wear rubber flip-flops for protection. During last week’s storm two boats on this finger were hit. A strike blew the through-hull out of one boat. Six inches of water inside before the owner, lucky to be aboard, could jump from his bunk. I saw him on the dock today. He looked like a man who’d seen god and was not too happy about it. How can a weather cell contain so much energy? It’s raining lightning.

—

Bridges out or closed, landslides on north shore roads, 36 inches of rain in Hanalei this week. And in the days following, winds to 40 knots in the channels. Still, the cruise ships come and go as if all is usual.

***

Today, from Starbucks.

Mixed cloud and decreasing trades from the NE. But only midweek. By Thursday, expect more trade wind advisories. Yesterday was dry, all day, first time in memory. This is my window. Will attempt departure tonight.

A Harley Rally in “Good ‘Ole KSA”

February 2, 2012

“Why would I post pictures of a Harley Davidson Rally?” I asked my sister. “Who’d be interested in that?”

“Brother,” she said, “It’s a Harley Rally in Saudi.”

—

How the iconic motorcycle had become embedded in American culture I could half understand. Big as Texas, Vegas-shiny, loud like New York and LA-cool. The Cadillac of motorcycles. As American as …

Old fashioned and now a non-sequitur is the 1970s car-company slogan “Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and Chevrolet / They go together in the good ‘Ole USA.”. But swap Harley for Chevrolet and the rhyme becomes free verse, the jingle fresh and true. What’s “Ole” is new again. Fitting is the fact that Harley is a company re-invented, pulled up by its own bootstraps. Chevy was recently bailed-out.

But why should Americans alone enjoy their wild west romance? “Live to Ride / Ride to Live” has broad appeal, after all. The horse made our country as, until recently, the camel made theirs. They have their own wide open, untamed spaces, love of a well-built machine on which to roam. Why shouldn’t a romance for the past find truck here? Why shouldn’t they also find this fun?

The day of this much-anticipated event dawned slowly. For weeks posters in Dhahran’s public spaces had invited all to join and to sign up early. Participation required a special-issue identification card. Which needed a current passport photo. Which needed processing. Which needed time.

Dawn came slowly because days earlier a dust storm had kicked up in Jeddah and was blowing all the way across the country. The Arab News reported traffic jams, collisions, falling trees in that city. School was suspended. Government urged everyone to stay home.

Makkah Gate near Shumaisi is hardly visible as motorists ride through the dust storm. (Arab News photo by Mujib Hussain)

The storm reached Riyadh about the time that city’s Harley chapter began its convoy toward the Dhahran event. They surfed it across country to the Gulf.

“Should we go?” asked Bruce, searching the window for any sign of sun. “We try not to ride in this weather…makes the lungs hurt.”

But the dawn of this much-anticipated event was too much anticipated to miss.

This is the Middle East a Westerner might not expect–communal, light-hearted, playful–even in adverse conditions.

Click here to see all photos of the Dhahran Harley Rally.

Thank you to Val and Lavonna for the photography and to everyone for such a fun event. A special thanks to Lavonna for letting me borrow her bike, for a month.

Back to Kauai Normal

From Saudi to San Francisco for a few days with the wife. Lovely to be with her at home. Lovely being home, except for the overcast and the cold. A year in the tropics had convinced my metabolism that its requirements were permanently relaxed, and being so suddenly called to attention, it reacted with palpable resentment. I shivered even with the heaters blasting.

Other things had changed while I was away. The stylish furniture in our livingroom was entirely new to me as was the flat screen TV big as a billiard table. The bookshelf on my side of the bed, the one filled exclusively with my books, was missing. My bedside lamp had abandoned my side of the bed and now stood smugly beside the new couch, and Joanna’s things covered my small desk, her protests that she had “just tidied it” notwithstanding.

“Remember, we were broken into while you were away…” offered Joanna by way of explaining the new arrangement.

“…right, and the thieves took my old paperbacks and left you a new TV,” I said.

“Not exaclty. But see, you still have the big red chair,” she said as she flopped into it.

“Where should I put my bag?”

“Not in your closet. No more room.”

Admittedly, the apartment had never had much sympathy for my belongings, Joanna’s being so much nicer, but I began to feel that in the past year the two had conspired to move me out.

“Any mail for me?” I asked.

“Only a jury summons for October,” she said.

And then, “If you are coming home, we might need a bigger house.”

If?

—

Joanna accompanied me back to Kauai where, for a long weekend, we fell into our usual routine. Hike, swim, shave ice. Lay on the beach, swim, shave ice. Go for a run, sushi for lunch, shave ice.

The frangipani-scented trades blew softly out of a blue sky and held up cottony clouds as if nothing could be easier. This must be what was imagined when the first people imagined heaven, I thought, even if the island’s wild boars do not lie peacefully with the endangered honey creepers, even if they still tend to eat things they shouldn’t.

“What do you want to do today?” asked Jo.

“Hold hands,” I replied.

“We did that yesterday.”

“Hike … and hold hands?”

–

—

After Joanna returned home, my friend Jim arrived. For ten days we were on the go in a way I had not experienced since my first few trips to Kauai.

We–

-Hiked The Sleeping Giant and Kuilau Trail.

-Toured the Haraguchi Rice Mill and Taro Farm in Hanalei.

-Hiked the Okolehau Trail in search of views, which we found, and mud and wild boars, which were accepted as part of the experience.

-Walked the McBryde Gardens in Poipu and later took a guide for the Limahuli Garden’s collection of canoe plants.

-Found the Makauwahi Cave which is the focus of David A Burney’s book Back to the Future in the Caves of Kauai

–Made Red Dirt Shirts in Nansy’s kitchen with her full knowledge and consent, tepid consent to be sure. Not this recipe, but better than Mike Rowe’s.

–

-Observed the Laysan’s Albatross, Great Frigate, Red Footed Boobie, White Tailed Tropic Bird at Kilauea Lighthouse wildlife preserve. While Humpback whales breached in the distance.

-Rented a cabin in the mountains of Kokee State Park and hiked the great Waimea Canyon to Waipo’o Falls; later we entered the Alakai Swamp in search of native birds (of which more here).

-Hiked the Kalalau Trail along the Na Pali Coast.

Each evening we returned to my in-laws home in Kapaa town to talk story over Jim’s fine wines. It helps to have a friend who is a wine maker.

I slept on the lanai because I finally had an excuse to, Jim having taken my spot in the guest room.

Then the rains came. They had begun that last day on the Kalalau Trail, a steady drizzle with thunder somewhere beyond the far mountains so muffled I mistook it for waves crashing on the cliffs below. But after midnight the winds shut down and the lightning started in earnest. Pop, pop, pop–the low cloud lit uniformly like a giant flash bulb. From my bunk I tried to close my eyes against the bright but found they were already shut. Then a few breaths before the rumble, soft at first like cannon fire out at sea; it rolled on and on getting louder and louder until it was like the exploding of the near mountain. Any moment I expected the house to be crushed by falling boulders. Sometimes the lightning was close and then there was no delay. The flash and boom were apocalyptic. I flinched.

And the rain poured. It gushed from the sky as if someone had upended the ocean.

I didn’t start counting till three in the morning. Hours on end lightning had been flashing once every twenty seconds or so, I found. By five I could count up to 45 seconds before the next strike. I thought the cell, a mushroom cloud bigger than the island, must be receding back into the ocean that birthed it. Then lightning would crack in machine-gun clusters like a fireworks finale. And after a pause, it would begin again its regular rythm. The charged sky was inexhaustible.

Just before dawn wind came off the mountains, and my place under the eve was no longer protected. A sprinkle at first, and I reacted by curling under the blanket. Then one gust and I was drenched–blanket, sheet, pillow, futon mattress, me–all soaked through. On this day I was the first to rise and make coffee for the house.

Lightning, thunder and rain continued all day and into the evening. Any waterfall that could fall fell. Rivers ran the color of carob and carried great rafts of dead wood from the hills. A real Kona Storm.

Composite Radar Image of Cell over Kauai (the square in the middle). Note Oahu off to the right, dry.

Mount Waialeale is Kauai’s highest peak and is reputed to be one of the world’s wettest spots. There are no roads to the top. Trails are almost immediately jungled over and always slick. The ascent is treacherous, and you won’t find it in the guide books. Thus the first USGS rain gauge placed at the summit in the early 1900s was meant to measure annual rainfall. But the gauge held a mere 300 inches of rain and upon inspection was found to be full before its time. The next gauge held 900 inches. It found that rainfall atop Waialeale averages between 389 and 423 inches a year.

On the day of this Kona Storm, Waialeale received over six inches of rain. The town of Anahola over eight. Lihue’s rainfall was an all time record.

I’ve moved back aboard the boat. A few projects need doing before Murre and I launch another run through the islands. But our Kona continues. Two nights ago lightning lit up Nawiliwili and knocked out the harbor lights. I gingerly trod the cabin in flip-flops, expecting any moment to hear the splitting of Murre’s mast. And the next day it rained like Noah’s curse. And now and still.

Dhahran, First Impressions

It may be a truism of travel that at base one place looks much like another. When I first landed in Kona, Hawaii years ago, I was disappointed to find the topography so similar to my native California. Shouldn’t it have been utterly different? Afterall, it was over 2000 miles away. That epiphany lead to others. The cloud soaked hills of Marin are like wandering similar hills in Scotland. Mexico City has the flavor of an ancient, future Los Angeles, Los Angeles a decayed Tokyo. The Farasan Banks of the Red Sea froth white with waves like those that crash on the Great Barrier Reef. Carl Sagan exclaimed at his first view of a new land, “This was not an alien world, I thought, I knew places like it in Colorado and Arizona and Nevada.” He was referring to Mars.* So I should have known.

Still, there was some surprise at finding that my sister’s neighborhood inside Dhahran’s mostly expat compound could have been in the suburbs of Phoenix or San Diego. Streets were regularly laid out, tree-lined, sidewalks wide and free of cracks. Every several blocks was a small park for the children or a duck pond and fountain. The neatly manicured golf course was ringed by a paved walking track. There was a heritage museum dedicated to Aramco history, a large library, two fine restaurants, a commissary jammed with western goods, a gymnasium with an olympic sized-pool, even a bowling alley. Two on-camp radio stations played American pop and American country music, respectively. Here, and nowhere else in Saudi, women of any nationality could drive. Western dress was the norm.

It was comfortable. It was like being at home. It was designed that way.

Muslim women often wore their black abayas on afternoon walks, even jogging, and contrasted sharply with others in their running shorts and tank tops. Groups of groundsmen from the sub-continent, all in yellow jump suits, roamed freely and napped in the shade for long periods after frenzied bursts of grass cutting or weed pulling. Their approach might flush a Hoopoe digging for insects in the lawn or a Bulbul or a Myna. Small mosques dotted the compound, following the age-old rule that all who wished should be within easy walk of a place to pray. The call rang out frequently, and then the groundsmen would wash hands and feet at the closest spigot, lay out their headscarves on the lawn and kneel, facing Mecca.

Saudi fighter jets roared low overhead any day except Friday, banking left and flashing the green ensign–a single simitar below the famous remark in Arabic script, “There is no god but God, and Mohamed is his messenger”. “The air base just beyond that fence is in high gear now,” said a neighbor pointing to a long runway obscured only by haze. “They’ve been at it constantly for weeks, but they bank left, always left. I hope that turns out to be the correct maneuver when the time comes.”

That these essential differences were folded into such a familiar framework made my head spin.

____

“Oh, you are so lucky!” was often repeated at my sister’s lavish dinner party.

Her social circle of expats included nurses, dental hygenists, accountants, grade school teachers, administrators, airplane mechanics, auditors, geologists, and engineers. A more diverse group under one roof I had never met, and all were handy at conversation, quick to laugh, and utterly welcoming. All went out of their way to congratulate me on the next trip. “You are going to dive the Farasan Banks? Almost no one goes there–you lucky man!

____

*Cosmos, Carl Sagan, Random House, 1980, Location 2178.

A Desert Interlude, Getting to Saudi Arabia

January 11, 2012

Saudi Arabia is effectively closed to westerners. Though as many as 100,000 expats–mostly from the US, UK, and Ireland–are employed in the various camps of Saudi Aramco, the national oil company, western tourism is unheard of. Even when one has the advantage of a sponsor, a sister stationed in the eastern province town of Dhahran these last ten years and more, the acquisition of a visa can be tricky. Add to this the short vacation times afforded the typical working American–Saudi is 170 degrees of longitude east of my home in San Francisco; recovery from jet lag would take a week–and the general unrest in the region as portrayed in western media, and one might sympathize with my delayed visit.

But with winter booming in the north Pacific and Murre tucked away safely in Nawiliwili, there was no better time.

“Your first step is to call our Houston office about a visa,” said my sister when I phoned to arrange travel. “Speak to Mr. Mahomet. I can’t do this for you. He’ll talk only to you. You’ll need to send him your passport. And be ready.”

Ready?

“You have not sent your passport I hope, “said a heavy voice when I rang Houston and stated my purpose.

“I have not,” I replied. “That’s why I’m calling.”

“You have a brother in Saudi?” asked Mr. Mahomet.

“No.”

“A father?”

“No.”

“You cannot visit unless you have family in the country to sponsor you,” he said.

“I have a sister who works in Dhahran.”

“A sister…hmm…but she is female…?”

“As I recall…”

“This may be difficult. Is she married to her husband?”

“Yes,” I said, momentarily unsure.

“And are you married?”

“Yes,” I said, and then quickly, “to my wife.”

“And your brother works at Saudi Aramco?”

“I don’t have a brother.”

“So your sister is not married to your brother?

“No, but…”

“Oh, this is not good,” said Mr. Mahomet sharply. ” As I said, the embassy will not extend a visa unless you have family in the country.”

“Let me clarify,” I said. “My sister and her husband–my brother-in-law–are both married, married to each other, still married, and both work for your company.”

“Ah yes, but do they live in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? Aramco is a global company, you know. For example, I am from Jeddah, but I work in our Houston office, this is in Texas, and we also have offices in New Delhi, Shanghai, The Hague…”

“Yes yes. They both live in Dhahran.”

“And you are married?”

“Yes,” I said, ” to my wife.”

“And it’s your wife’s brother who is married to your sister?”

“Nope. My wife’s only related to me. Not by blood, mind you, she’s not my sister or even a cousin or anything like that…”

“Cousin! Now you are confusing matters,” said Mr. Mahomet.

“… but I mean my wife has no family in Saudi. My wife’s really not in this. She’s not going with me. It’s just my family in Saudi.

“Your brother and sister.”

“No.”

“Good,” said Mr. Mahomet after a pause, “here’s how we’ll proceed…do you have a pen? You’ll need to take notes…”

In addition to my passport, Mr. Mahomet would need to prove my existence and my relationships with a copy of my birth certificate, my marriage licence, a copy of my sister’s birth certificate and that of her husband, their marriage license and the their work visas.

“That’s quite a list,” I said, gasping.

“Not done,” said Mr. Mahomet. “I will fax over a three page application that must be completed entirely. It must be sent in with the above and along with two additional, current passport-type photos, not large, but passport size. If you look different now than when the original passport photo was taken, that needs to be explained in a note appended to the photos. Please sign and date the note.”

“I need to explain to you why I now have a beard as long as Abraham’s?” I asked.

Mr. Mahomet did not laugh. “Now,” he said, “I need all those documents, in that order, overnighted to my office in one package. Do not send things separately–they will get lost (Mr. Mahomet did not say by whom, but I had a hunch). It would be best if they arrived before Friday.”

“And how long before I get the visa?” I asked.

“Well,” he said, “we must wait for approval first. Maybe one month. Maybe two. Many things must be checked. Not long.”

I deplaned in Frankfurt in the gray of dawn, heavy with the fud of a New York red-eye and craving to commence my six-hour layover with an espresso and a croissant. With some surprise I observed that my much-anticipated first experience of northern Europeans within their own boarders would be a group of white-shirted German businessmen crowding the airport bar, heaving up yellow ale from tall glass steins, and wolfing red sausages whose rich odor had penetrated even the jetway. From such a breakfast, I wondered, comes the precision of German engineering? “It is zee lunch,” stated the bar tender when I asked about a poached egg and toast. I had been mistaken about the time–the quality of morning light being the brightest a high-latitude winter can produce.

Night was full when my Lufthansa flight made its bee-line for Dhahran. On the TV monitor our virtual plane passed over Turkey and Cypress before jogging right to avoid troubled Syria 39,000 feet below; then a straight southeast course was resumed, and we passed quietly over the vast, black reaches of empty Arabia. The attendant had brought dinner accompanied by generous pours of red wine, but as we crossed into Saudi air space, dry as a desert by religious decree, our glasses were retrieved and a pad lock clicked over the liquor cart. Next a customs form was distributed which contained, along with the usual requests for information, a box for my mother’s maiden name and my religion . These had featured prominently on the visa application completed months before, but that form had also required I divulge my blood type, my university and GPA–anemic, slacker-atheists of a certain family line were unwelcome, would at least be watched closely.

Stamped at the head of the customs form were bright red letters that resolved into the sentence, DEATH TO DRUG TRAFFICKERS, and served to remind that my country of intent was not of the usual sort. I am not a drug trafficker; I am not even a hobbyist, but as we touched down at King Fahd International Airport, my mind raced through the bag I’d checked and wondered if a generous supply of aspirin or mouthwash would damn the likes of an anemic slacker atheist.

Midnight and the airport was quiet. Its grand hallways, plushly carpeted and doors of gold, had the air of an old, abandoned casino. But instead of slot machines, here and there, prayer nooks were cordoned off. At the customs room, uniformed young men huddled, talking softly over their rifles as the Germans and I formed one long, neat line. We waited in silence. Our flight’s only female, a mother with her husband and two children, excused herself to use the toilet and returned in a full abaya. A Saudi couple, both in traditional garb, entered and walked directly to the head of the line. They were waved through by the officer-in-charge without so much as a second glance. He appeared to be in his late twenties; the officer manning the customs booth was even younger. The line crawled.

Then with a whoosh the room filled with a hundred short, dark men in pastel tunics. Another plane had landed. “Laborers from Pakistan,” said my neighbor, “they do all the work around here.” The men wore heavy coats against the cold (70*) and black dress shoes. Suddenly the officer-in-charge came alive. He barked orders and another booth opened. He barked again, and the tuniced men moved haltingly to form two lines. He barked, and the lines attempted, with poor results, to become orderly. He waved a customs form above his head and the men, realizing none had it, abandoned their lines and moved bodily off to a corner desk. Forms fluttered into the group, and the men gathered into large knots, sharing in turn the three pens they had brought with them.

My opportunity came at last, and I handed my papers to an officer whose face was more fuzz than whisker. He did not look up, but talked with the inflated authority of youth into the headpiece of one cell phone while he punched texts into another. He nodded toward a camera and my picture was taken. He motioned, palm down, at the glass desktop where I put both hands and each digit was recorded by a green light three times. He checked his computer screen. Then he leaned back casually cross-legged to talk and text for several minutes. The screen beeped. He leaned forward without coming out of his relaxed posture, stamped my passport with the hand not texting and I was through. He had not said a word to me.

“DEATH TO DRUG TRAFFICKERS…”, I repeated as my luggage was lifted from the X-ray belt by yet another boy-officer whose only concern was to double with laughter at an obscure joke told by his partner. My bag and I passed without notice to the main gate, beyond which the press of Pakistani men awaiting their companions formed a narrow, undulating gauntlet at the end of which my smiling sister in her abaya and her husband in a yellow polo shirt stood out in absurd, welcome relief.

A Desert Interlude

- Getting to Saudi Arabia

- Dhow Diving the Red Sea (coming soon…)

- Riot Free Bahrain (coming soon…)

- A Goat Grab in Hofuf (coming soon…)

- Avoiding Arrest in Madain Saleh (coming soon…)

“Did you drown?…”

“Has the story ended? Did you sink the boat? Did you drown? ” wrote a concerned friend recently.*

And no wonder.

After almost daily posts to this blog for months, on coming ashore in Kauai I just stopped. Every thing changed. I moved in with my in-laws and spent a month in paradise on nothing but boat repair. I flew home to California and Texas for the holidays. Then there was the month in Saudi Arabia, a storm on the Red Sea and a brush with the law in Al-Ula. It was a heady time. I couldn’t keep up.

“You should make sure your audience is with you,” scolded a relative. Far be it from me to mention that “my audience” is mostly relatives–my mother, my sister and her geologist friend, one aunt in Canada and another in Orville, a few cousins, a friend and his mom–none of whom, save the geologist, have ever needed this blog to know my whereabouts.

But point taken. After all, I’m the one who started this.

So, after two months away, tomorrow I return to Kauai and Murre.

_____

*Should I respond to that email?

What Happened Next

November 8 through December 11

The disappointment of finding myself alone in a familiar harbor quickly evaporated. Peter and Nansy arrived before I’d switched off the engine, Nansy carrying a Ti leaf lei and Peter a broad smile and a handshake. That they had not met me earlier was my fault, I now recalled. Predicting the transit time of a small, wind-driven ship is futile, so I’d promised to alert them by phone as we made landfall. But Murre’s jockeying with a cruise ship at the harbor entrance distracted me, and I had failed to keep my part of the bargain.

Greetings were immediately followed by breakfast at a local restaurant where stacks of scented pancakes, eggs and bacon and endless hot coffee erased any memory of missed expectations. The sun shone, and a warm wind smelling of flowers ruffled the palms. I was on the dry land of an island I called home. I couldn’t stop smiling.

“Our house is yours–stay with us as long as you like,” they had said, and I wonder now if they later regretted such an open invitation. Because I moved right in, digging deep into the luxury of a real bed with soft, clean sheets, hot showers that required nothing more than the opening of a faucet, and home cooked meals, rich soups with fresh breads and brie and pickled herrings marinated in dill as accompaniment (the latter reflecting Nansy’s Norwegian heritage). From their lanai I could gaze out to the south and the ocean I’d just crossed; to the west was the bold line of mountains above Nawiliwili under which Murre relaxed in her berth, and to the north that range whose cloud covered peak, Mt. Waialeale, I knew to be the wettest place on earth. It was delicious. I stayed a month.

By design it was a busy month. After so long on the go and under the hot tropical sun, Murre was the worse for wear. Her toe rail varnish, entirely neglected since leaving San Francisco, had baked or blown off ; the paint of her coach roof crackled and curled; the beating mainsail and its batton pulled paint off the mast in chunks, and a year of rock and beach landings had worn down the dinghy to bare wood. During the passage to Hawaii, two of the five solar panels had ceased to function; the bracket holding the engine’s oil filter in place snapped, and deck leaks had soaked many of the cabin’s cushions, which now smelled of mildew. Maybe most importantly, weather on this leg north emphasized the need to protect the cockpit hatch from breaking waves. The list went on and on…

__________

Luckily the welcome of my in-laws included the offer of power tools and their proper, open-air shop. Peter is a sailor and a boat builder in his own right. Years ago, Nansy and he constructed a river barge of forty feet outside their home on the Deben near Woodbridge, England. Here a gleaming but empty black, steel hull gave rise, as if by magic, to decks of varnished teak and an elaborate interior designed for entertaining, as if by magic because while these two were building this boat on the hard, they were also rebuilding the house it sat next to. This was before they retired. Once completed, the barge became Albertine, and on it they cruised the canals of France until there were none they hadn’t seen. Kauai’s waters are no place for a barge. So when they moved to the islands, Peter switched his focus to the traditional craft of the tropical Pacific. In his shop was a twenty-five foot proa nearing completion.

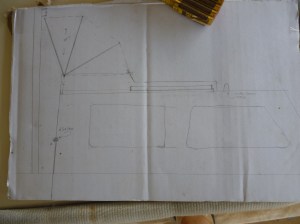

The shop began to look like Murre had also moved in. The cushions for steam cleaning, their slats for painting were scattered haphazardly about. The dinghy and her oars pushed the car into the drive, and here they were sanded down, reglassed and brightened with fresh gloss. The storm windows, knocked uncleverly from plexiglass at the dock in La Paz, were trimmed and neatened. As to the cockpit hatch covering, I was of several minds, but consultations with my two hosts landed us on a small, tough cuddy with a canvas hood, which soon began to take shape from a single sheet of plywood.

My previous work on Murre was, I liked to think, extensive and well executed–a cockpit rebuilt, a length of deck relaid, a bulkhead removed and renewed. But all this work was confined to replacing things that existed. The old was the pattern for the new and so my imagination had remained mostly untaxed. The cuddy design, however, needed inventing from thin air, and I was frequently at a loss how to proceed. As I stood befuddled over the construction table, I’d often find that Peter had softly sidled up. “Yes,” he would say, “I can see where you are going with this. The top will be nicely strengthened with the epoxy fillet and that extra rib,” neither of which I had yet contemplated.

We rose early each morning and gathered, coffee cups steaming, on the east lanai to chatter softly about the coming day and to watch the sun rise. Once it was so clear we could see the hump of Oahu above a sharp, slate-gray horizon, but usually a sweet haze prevented seeing such distance, or towering cumulus filled the ocean and required the sun fight its way through. Trees along the near bank also obscured its rise, and often Nansy talked about which should be cleared in order to improve the view.

Then, before breakfast, we would dash to our tasks, I to the shop and Peter to his garden, or they two would attack the offending arbors before the day got too hot for hard work. Afternoons were reserved for books and napping, evenings for parties. Time flew.

The basic idea was to build a small cover over the companionway hatch with a hood that would allow me to sit under it, dry in all weathers.

The hoops that would support the hood were made of several layers of 1/4" ply cut to into 1 1/2" wide strips and laminated into their correct shape around a frame of shaped 2 x 4s.

Once knocked up and hoops built, a second fitting to the boat, the purpose of which was to get right the height. I sat under it to make sure before cutting the top and hoops to final length.

![dahran-saudi-aramco[1]](https://murreandthepacific.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/dahran-saudi-aramco11.jpg?w=600&h=246)

![Yotreps_Big_Map_3[1]](https://murreandthepacific.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/yotreps_big_map_31.jpg?w=600&h=607)